We are now in the closing hours of 2018. One of the aspects of life today (and I am sure it will be true in 2019 as well) is that we rely so much on experts to address the various questions we face. Health issue? See a doctor, and if (s)he does not know, you can get a referral to a specialist. Computer problem? You find either a hardware or a software expert to help you. In almost any area of life we turn to experts for advice and help

. This usually works out, but sometimes blindly following experts can lead us into a worse predicament. Witness our ongoing global economic crisis – instigated first by the ‘experts’ running US financial institutions, and more recently by the ‘experts’ who configured and managed the Eurozone. It is interesting that there are thousands of expert economists who make a living giving us economic advice … and maybe about a dozen of them saw the economic disaster coming.

So it pays to have practical and common-sense checks to test against the advice of experts. This is all the more true when it comes to claims and statements by ‘experts’ when it comes to the Bible. Bart Ehrman is one such New Testament scholar who has gained much notoriety for his public attacks on the gospel. The title of one of his books, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (2005) tells us what he thinks of the reliability of the text of the Bible. And since he is one of these ‘experts’ who are we to argue? For many, just reading the title of his book closes the case for them.

But New Year’s Eve 2018 is a last-minute reminder of a common-sense and reasoned test for the reliability of the Bible. For 2018 is the 407th anniversary of the publication of the Authorized King James Bible. Yes, this translation that has so shaped the English language through modern history is on the verge of passing its 4th centennial!

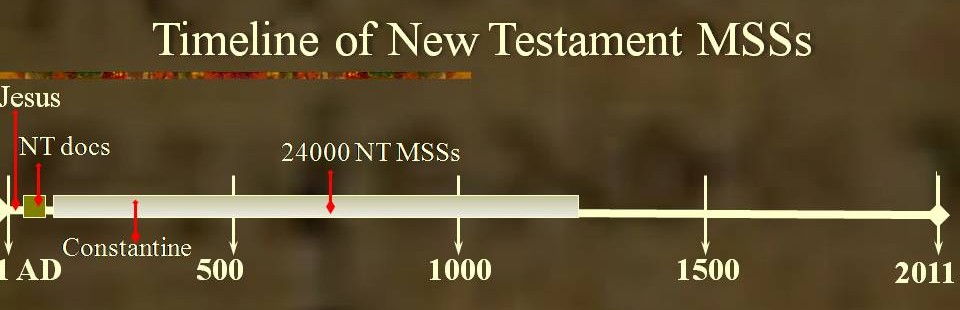

The timeline figure below from time of Jesus until today shows the extent of the time period in which the 24000 manuscripts of the New Testament that are extant (i.e. in existence today) were being copied (the thick white bar labelled ‘24000 NT MSSs’). Extant copies are dated starting from 125 AD and continue until about 1250 AD. This is what we covered in Session 3. No one – Bart Ehrman included – disputes this.

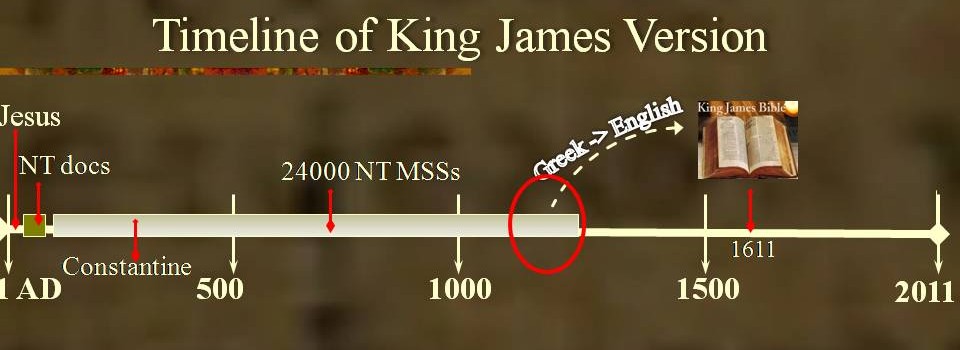

Our next figure shows the manuscript source for the venerable King James Version (KJV). It was a 16th century scholar named Erasmus who first produced a Greek text from which the KJV was translated. But where did Erasmus get his Greek text? As you can see from the red oval it was from a few very late Greek manuscripts, dated well into the 2nd millennium, from which Erasmus obtained his text (called the Textus Receptus or Received Text) and from which the KJV was developed. No one disputes this – Bart Ehrman included. In fact, his book is an easy-to-read description of how this transpired.

The reason that Erasmus used just a handful of very late manuscripts for his Greek Edition was that in 1515 AD no others were on hand. He used the best he could find. But since 1515 AD thousands more have been discovered (which is why we now have 24000 manuscripts catalogued) and many much earlier, even preceding Constantine (325 AD).

Our third figure shows, with this modern catalogue of manuscripts to draw from, the manuscript source for present-day translations (like NIV, ESV, NLT etc.). They draw from the earliest and best manuscripts that scholarship and archaeology today provides, and which were unavailable to the translators of the KJV in 1611. Again, this was covered in Session 3, and as with our other points, no one today – Ehrman included – disputes this.

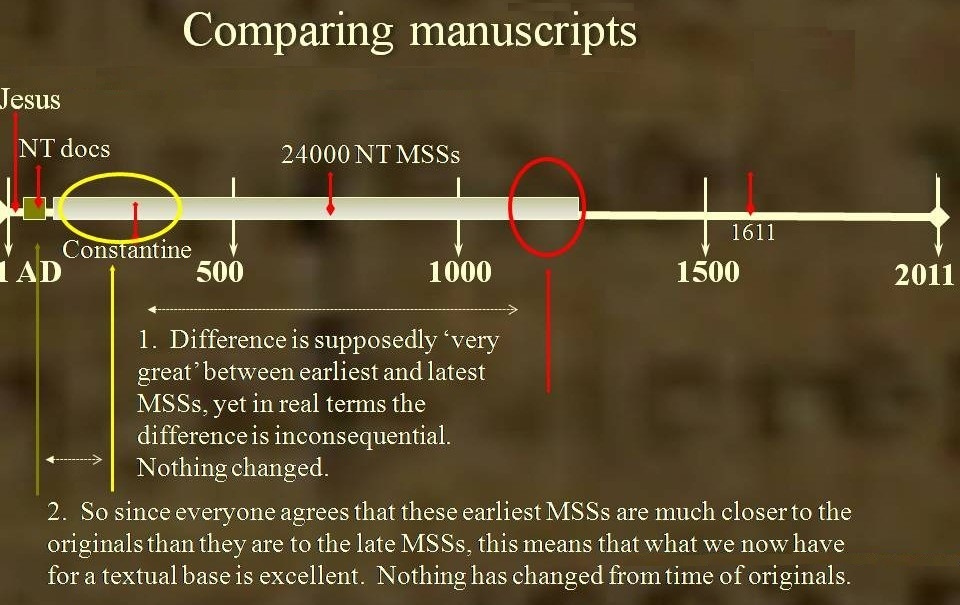

To put it in another way – the translators of the KJV used (by today’s scholarly standards) the latest and least reliable manuscripts (their source manuscripts were later than 1000 AD). And today we know we are very close to the original text with an extremely high standard (see session 3) because of the much earlier texts that were discovered after the making of the KJV. So these advances give us a superb common-sense and practical way to test the reliability of the New Testament. We simply need to ask the question: What teaching or belief changes took place when gospel followers went from the KJV (the least reliable) to the modern versions (the most reliable)? Was the person and work of Jesus, the historical events portrayed, or teachings outlined in the epistles ‘adjusted’ in some way? For example, was there anything even remotely close to an adjustment on the order of a Da Vinci Code? No! In point of fact nothing changed! Today you can find gospel followers worldwide – some using the KJV and others using a modern translation – and no difference in their understanding or following of the gospel come as a result of their divergent translations.

Our fourth figure illustrates this schematically. We know (in step 1) that what is purported to be ‘very different’ by scholars such as Ehrman is in reality a small difference since the KJV teaches the same thing as the modern translations. So therefore (in step 2) we know that what is now a smaller difference between our current textual base and the originals must be small indeed. We have a solid textual base and can confidently say (Ehrman notwithstanding) that the Bible has not changed.

The same test is available for the Old Testament. In 1611 the only practical Hebrew text for the Old Testament was the Masoretic text dated at around 900 AD. The most modern translations of the Old Testament can make use of the Dead Sea Scrolls dated at 100 BC. (We look at the Old Testament in the 2nd video of Session 3). And you will find no ‘adjustment’ in the history and teachings between the KJV and these modern translations. They tell the same account.

Ehrman’s book title aside, and despite his intent to denigrate the textual reliability of the Bible, his own account of the textual development of the KJV, and a common-sense check for any ‘adjustments’ in teaching or belief stemming from the KJV to a modern translation reveals the hollowness of his claim. Sometimes it pays to not to blindly accept ‘expert’ opinion by faith like so many do today. Common-sense reasoning from the verifiable facts on-hand is the safest way to go. On the passing of the 400th anniversary of the KJV It is a good reminder that it provides us with a dataset with which we can consider the gospel in just such a way.